Outdoor Movie Press Articles

A movie experience as big as all outdoors

By Claudia Puig, USA TODAY

Movies Under The Stars

By DANIELA ALTIMARI | Courant Staff Writer

August 19, 2005

WEST HARTFORD -- The audience arrived at dusk, gathering on the grass behind the public library with lawn chairs and popcorn and, occasionally, a pajama-clad toddler in hand.

They came for the 8:30 showing of "The Incredibles," and even though most seemed to have seen it before, the allure of an outdoor movie on a soft August night proved irresistible.

"How great is this?" Sarah Lemieux asked, surveying the scene from her blanket. "We even brought our dog."

Evoking an old-fashioned drive-in - minus the cars, of course - the lawn behind the library in Elmwood became an al fresco cinema Wednesday night. The concession stand was a folding table staffed by a civic group selling 50-cent cans of soda; the screen was the freshly painted cinderblock wall of the sprawling Puritan Furniture store next door.

Long a tradition in Europe, outdoor movies are becoming a summertime staple in the United States. Detroit, Cleveland and Chicago are among the dozens of big cities that show films in public parks. In Washington, the Mall becomes a giant, open air screening room every Monday night in July and August. And in New York City's Bryant Park, movie lovers begin staking out blanket space hours before the film rolls.

Now smaller communities from Colorado to Connecticut are discovering that some projection equipment, a patch of grass and a night sky freckled with stars are all they need to bring people together. Like the weekly farmer's markets that have sprung up everywhere, it's an old-world idea that captures vaguely nostalgic notions of small-town life, before the arrival of the big-box store and the 20-screen multiplex.

"People are looking for places to go, particularly in the suburbs," said Kathy Madden, vice president of the Project for Public Spaces, a New York-based non-profit group that promoted programs for parks and other community resources. And, she noted, most outdoor movies don't charge admission.

The operators of a thriving outdoor cinema in Boulder, Colo., have received calls from people all over the country wanting to replicate their success.

"It's been catching fire," said founder Dave Riepe. "Drive-ins have faded away, but there's nothing like watching a movie outdoors."

The Boulder Outdoor Cinema, launched in 1995, sometimes draws as many as 900 people. "Movies have always been magical mediums," Riepe said. "Communities are starting to recognize that [they are] a way to bring neighbors together."

Rocky Hill began its summertime film series a couple of years ago, and now the weekly fresh air gatherings in an amphitheater in Elm Ridge Park draw 150 to 200 people "depending on the movie and the weather," said Chris Rusack, recreation supervisor. The final show of the season, "Shrek 2," begins tonight at dusk.

"Everyone's so busy nowadays," Rusack said. "This is a way for people to connect."

Unlike the cities, where edgier, artsier offerings prevail, the suburbs tend to feature family-friendly fare, the latest Disney release, perhaps, or a Harry Potter adaptation. And even though the films are not new releases, watching a movie on a lawn chair in the moonlight is so much cooler than watching a DVD on the couch in your living room.

"It's a little like an old-fashioned drive-in," said Marcia Lewis, librarian at the Faxon Library in Elmwood, which sponsored Wednesday's "Incredibles" screening. Drive-ins are as rare these days as fins on cars, but `'we were hoping to capture their spirit," she said.

The neighborhood has not had a movie screening since the Elm Theater closed in 2002, and residents cheered the return.

Of course, watching the film play out on the side of a furniture store is nothing like seeing a movie in the darkened cocoon of a theater. Out here, the scent of bug spray hung in the air and traffic on nearby New Britain Avenue whooshed by. Streetlights cast a distracting glare and there were no ushers to shush the many chatting adults and the occasional crying child.

Still, most of the crowd would probably not want to be anywhere else. "This is such a great idea," said Hasan Samakaab, who came with his 7-year-old daughter and several other relatives.

For Samakaab, the experience conjured childhood memories of watching movies outside in a soccer stadium in his native Yemen. "The whole community would come," he said.

Others, like Mary Ellen Wilkinson, were reminded of piling into the family car and going to the drive-in. She still remembers seeing "Bedknobs and Broomsticks" as a little girl.

Sarah Lemieux brought her children so they, too, would grow up knowing the joy of seeing a movie outdoors. "This is just like when we used to go to drive-ins," she said. "How fabulous is that?"

Copyright 2005, Hartford Courant

Summertime, the living is easy, the nights are warm and outdoors in a cemetery is the place to be. Unless you prefer bobbing on an inner tube or picnicking in the foothills of the Rockies.

|

Actor Jon Voight and director Michael Mann, left, set up picnic to watch movies under the stars. | ||

| By Dan MacMedan, USA TODAY | |||

Of course, one must be willing to brave the elements — if not the insects — that can add unexpected excitement to the al fresco moviegoing experience.

Outdoor theaters are an increasingly hot (and cheap) summertime ticket in most states around the country. Prices range from free to $10 a person.

"America has always had a love affair with the movies and with outdoor entertainment. Now the two have come together in the contemporary version of the drive-in," says Bob Deutsch, who organizes outdoor film festivals in Maryland and Virginia.

Some movie fans set up beanbag chairs in a parking lot in Olympia, Wash. Others share a well-manicured lawn with ghosts of silent movie stars in a Hollywood cemetery. Some float on inner tubes on a lake in San Antonio, and others blow up beds in a park at the foothills of the Rockies or spread blankets on the sand while roasting marshmallows in Newport Beach, Calif. There are more than 100 major open-air theaters around the USA, Deutsch says.

"People bring whole dinners — chandeliers, candelabras, wine, hibachis, everything," says Brian Cobb, executive director of Way Out West Productions in Olympia, which has been showing movies outdoors for three years. "It becomes a tailgate party/flea market and a movie experience."

At the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, about 1,500 people gather twice a month on Saturday nights to watch classic films "beneath and above the stars," says organizer John Wyatt. Movies are projected on a marble mausoleum wall, near the graves of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Sr., Rudolph Valentino and Cecil B. De Mille.

Alexis Scott celebrated her birthday there, sharing blankets, pillows and an Asian-flavored picnic dinner with three friends.

"It's always really beautiful here watching the palm trees and seeing the movies," Scott says. "It's a great communal feeling."

Watching a story unfold by moonlight has special appeal. Call it Cinema Paradiso, American style.

Hollywood Forever Cemetery is an oasis in the middle of an urban Hollywood neighborhood. Close to studios such as Paramount and Warner Bros., the venue attracts industry insiders like actor Jon Voight and director Michael Mann, who were there on a recent Saturday.

Mann has been to the movie series four or five times, drawn by classic films like Sullivan's Travels and Sweet Smell of Success in the open-air setting.

Voight, who munched on tomatoes and mozzarella, says, "It's a wonderful thing to see a film the way it should be seen, which is in a group. And out of doors in an informal atmosphere and near the Fairbankses and all these people who have contributed to our industry in another era just adds to the atmosphere."

Mann's assistant, Julie Herrin, wasn't quite as enthusiastic about the ghosts of movie stars past. "Being in a cemetery is a little freaky. I hope we don't walk on anybody."

But Polish-born Alexander Gruszynski says he finds it nostalgic, "like a piece of Americana that got lost. The concept of drive-in theaters ceased to exist."

Something about being outdoors relaxes people.

"People bring their own chairs and can hoot and holler at the screen where they cannot in a movie theater," Cobb says. "It's more interactive."

And some movies benefit from that atmosphere.

"You get more from the experience when you're laughing with 500 other people sitting right next to you," says Dave Riepe, who programs an outdoor film series in Boulder, Colo.

At Hollywood Forever Cemetery, DJ David Hollander spins "tunes for a morbid night" at the cemetery that dates to the late 1800s.

"I went there to see one of my favorite movies, Sweet Smell of Success, and it dawned on me that it was entirely possible that some of the actors who appear in the film were buried in sight of where I was sitting," says journalist and outdoor film buff Chris Willman. "If one were to believe in ghosts, it'd be fun to imagine some of the actors interred there coming out to watch themselves on screen."

All outdoor venues don't have quite that kind of cinematic synergy, but they draw die-hard fans.

In Brooklyn's Prospect Park last month, a record 6,000 people showed up to watch Creature From the Black Lagoon in 3-D to kick off a Brooklyn arts festival.

Most outdoor theaters show movies appropriate for the whole family. Ikea, the furniture store, sponsors weekly outdoor screenings in Burbank, Calif., of such family films as Shrek and Jurassic Park. L.A.'s Chinatown is hosting a Jackie Chan film festival this month.

"The ones that are great to watch outdoors on a big screen are adventure movies like Lord of the Rings, Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lawrence of Arabia," Riepe says. "The parents love it because they remember going to see movies outdoors at drive-ins as kids. Now they want to take their kids to something similar."

Cobb in Olympia targets another key demographic: "Our rule is 'Is it a good date movie?' We generally stick with some new releases and sure-fire classics. There is also the trend toward Mystery Science Theater nights, where the actors come out and pan a B movie."

And people from the USA to Canada are looking to start their own outdoor cinemas. "We've had calls from virtually every state," Deutsch says.

Little wonder, since most states have natural settings that lend themselves well to star-lit films.

"If you love the movies and you love the outdoors, al fresco cinema really is kind of the best of both worlds," Willman says. "Movie theaters have traditionally been designed to take you away from the real world. But there's something interesting about seeing a movie screen integrated into an outdoor landscape. It's incongruous and fun, seeing these oversized images plopped down amid real life, as if the gods were paying an unexpected visit."

But the gods also can wreak their own atmospheric havoc.

"We still show a movie in light rain, though it definitely does have a slimming effect on audience size," Riepe says.

Scott and her friend Sandelle Kincaid were at Hollywood Forever a few weeks ago when an invasion of June bugs threatened to steal the thunder from the 1941 classic Ball of Fire.

"All these bugs hatched and got all over people's blankets," Kincaid says. "People were jumping and screaming and running away."

Adds Scott: "It was like The Birds."

NEW YORK TIMES - Front Page July 30, 2001

Stars on the Screen, the Moon Up Above

By SOMINI SENGUPTA

The suburban drive-in movie theater — that iconic site of American adolescent lust — may have gone the way of the Partridge Family. But few things being sweeter in summer than watching movies in the moonlight, New Yorkers are spreading their blankets and kicking off their workday shoes to relish the romance of open-air cinema again: On rooftops, along riverbanks, in neighborhood parks, free outdoor film screenings have sprouted all over the city in recent years.

If the drive-in was the ultimate symbol of 1950's car culture, cinema alfresco is an urban rite. In a city where a stoop counts as outdoor space, where the touch of cool grass at twilight is so rare it could well be bottled for sale, the popularity of outdoor screenings is a no- brainer.

Alyson Baker, executive director of Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, which holds a Wednesday night film series overlooking the East River, broke down the basics. "It's an opportunity to be outside, picnic, be cool and watch the sunset over Manhattan," she said.

Long common in many European cities, most famously in Locarno, Switzerland, whose Piazza Grande is converted into a giant open-air screening room for an international film festival every summer, outdoor films have popped up on this side of the Atlantic, from Baltimore to Boulder, Colo., to Berkeley, Calif., over the last several years.

The Mall in Washington offers a Monday night series. And in a grassy amphitheater on the campus of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., a 10-day series gets under way next month with a lineup of family-friendly fare. (With a nod to Bethesda demographics, the organizers even got the PG version of "Saturday Night Fever"; still, they hope that parental discretion is used the night "The Godfather" is screened.)

In Bethesda, the memory of a bygone era is part of the pitch. "Our goal is to recreate the days of the drive-in," said Bob Deutsch, the event manager hired to organize the series. "We try to link it up to that memory."

What is singular about open-air cinema in New York City is the sheer scope of offerings. With a combination of giant corporate sponsors and community-minded pluck, a surfeit of arts institutions eager to organize summertime screenings and movie buffs eager to watch the most deliciously arcane film, there is at least one free movie to watch every night of the week. (Lacking corporate patrons, a homegrown film series in a playground in Little Italy died earlier this summer.)

There are films with a Brooklyn flavor in the armpit of the Brooklyn Bridge, cult films on the piers jutting out into the Hudson River, independent and international fare in a small green oasis amid the red-brick forest of Astoria, Queens. In Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a clutch of loft dwellers mount a homemade sheet-metal screen on their roof every other Friday.

The other night at Prospect Park, where "Metropolis," Fritz Lang's 1926 silent dystopian look at city living, played on a 21-by-50-foot screen, Dianne Stills, 24, when asked to explain the evening's appeal, offered a puzzled look. "It's like silent movies, orchestra, Fritz Lang — C'mon!"

"There's French fries and ketchup," her pal, Dawn Brighid, 32, chimed in. "You can smoke a cigarette," which she did, as she sipped a can of Amstel Light.

The "classics" — those movies that everyone is supposed to have seen — have become the staple at most outdoor film series.

Curators and moviegoers alike say there's something about the giant screen and the sweating multitudes and the stars trembling overhead that lend themselves to the familiar. "They sort of appeal to the audience's imagination," said Jack Walsh, president of Celebrate Brooklyn, the nonprofit group that organizes performances and screenings in Prospect Park.

For the imaginative curator, they also offer opportunities for creativity. Two weeks at Prospect Park "Metropolis" was accompanied by original music, and last week two performance artists told stories through twilight, and only when the sun was safely beyond the horizon did the feature attraction, "Rebel Without a Cause," come on screen in all its garish Cinemascope glory.

Multiplex fare this is not, and therein lies its appeal. Not just any movie works outdoors. "Maybe a Reese Witherspoon, maybe that would work," Ms. Stills mused. "B- movies would work really well. Movies that are dark and twisted."

In her corner of the park, the crowd was engrossed in the dark twists of "Metropolis," hissing at the bad guy, gasping at scenes that first surprised 75 years ago. All evening long, a few strays lined up before vendors who offered cups of cheap wine, sweaty cans of cold beer, heaping plastic foam plates of fried chicken and candied yams.

The grand pooh-bah of outdoor cinema in New York City is, of course, the Monday night series at Bryant Park, which began nine years ago and is so popular that grabbing a spot means showing up hours in advance. And so a selling point of other film series is that they are not Bryant Park.

At Socrates Sculpture Park, on the water's edge in Long Island City, for instance, neighborhood residents cycle in at dark and plop down on the grass, just as the film is starting. On a good night, the crowd hovers around 400, compared with several thousand at Bryant Park.

The challenge here is the very magic of the setting. The lapping of the water and the twinkling lights across the river are a mighty distraction from whatever is on screen. That led David Schwartz, who chose this year's films, to select ones that lent themselves to the ambience — mostly films with and about music, like a documentary about a Greek clarinetist one week, a febrile Argentinean dance film the next.

"I didn't want to pick films where people have to totally pay attention to what's happening," said Mr. Schwartz, who is also the chief curator of film at the American Museum of the Moving Image in nearby Astoria. "You kind of want to look around, look at the sky."

Wall Street Journal Weekend Section

July 26, 2002 - Movies By Moonlight by Robert J. Hughes

A popular new communal summertime activity is seeing movies out in the open. Cities around the country are showing nighttime films, often for free, just after sunset. It's like going to the drive-in, without the convertible. The viewings often feature prescreening entertainment and music, too. Here are some options for cinema under the stars:

Comcast Outdoor Film Festival - Free films for food causes. Thousands turn out for this free movie series in Maryland, this year held on North Bethesda lawn between American-Speech-Language-Hearing Association and the Strathmore Center for the Arts. The only cost is for food prepared by local restaurants. Proceed go to charities of teh National Institutes of Health....

The Street Gets Star Treatment (LA Times 10/16/2003)

Outdoor movies have become the hook to draw people to tired business districts and public spaces. The reviews have been good.

By Shawn Hubler, Times Staff Writer

SAN FRANCISCO — Who holds a neighborhood mixer after dark in a vacant lot in the Lower Fillmore? Junkies were staggering around on the street. A cold wind was toppling trash cans and rattling the movie screen some optimist had hung on the side of an apartment building. And yet, against all conventional wisdom, a crowd was gathering.

Here they came in thick sweaters and leather jackets, with wine and lawn chairs and homemade popcorn in brown bags. Some came out of curiosity. Some came with their children. Greg M — "just M, I got the driver's license to prove it" — came by accident as the opening credits flashed on "When We Were Kings," the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman documentary that the city redevelopment agency had hoped would bring someone, anyone, to this blighted corner.

So intrigued was he by the sudden spectacle that he called his wife on his cellular phone.

"Hey, baby, they got a party going on down here on the street. You got to come on down here," he said with a chuckle as about 75 people whooped and cheered in the late-September night the way people rarely do anymore at the movies. "Down! Goes! Frazier!" barked the on-screen voice of Howard Cosell as 75 pairs of cold hands applauded. Next to a space heater, a grizzled man in a wool cap hollered, "Yessir! Good Lord!"

Welcome to the latest in urban renewal — outdoor movies. Fueled by nostalgia, redevelopment grants and advances in technology, alfresco movie screenings have, in a scant couple of years, quietly become a summer — and spring and autumn — fad from Walla Walla, Wash., to Washington, D.C.

"They're the contemporary iteration of the drive-in," said Bob Deutsch, whose outdoor movie business has more than tripled in the three years since he launched it. Deutsch, based in suburban Washington, D.C., said he set up outdoor movie series in 14 communities in the mid- Atlantic region this summer. He recently launched a sideline selling screens for outdoor viewing.

"The growth rate," he said, "has been phenomenal."

In Burbank, for example, a shopping center's need for midweek foot traffic burgeoned this year into a summer film series that drew 3,500 people a night to the side of an IKEA building — and into the mall — and prompted inquiries from communities as far away as Henderson, Nev., and as nearby as Irvine.

Two years ago in Baker City, Ore., a desire to bring locals back to a historic but neglected downtown resulted in a summer festival centered on a singalong screening, in the middle of Main Street, of "Paint Your Wagon," which was filmed there. "Small-town historical events can have a hard time," said Beverly Calder, a board member of the Historic Baker City Inc. economic improvement district. "But a bad musical with Clint Eastwood? That's something different."

L.A.'s Chinatown showed Jackie Chan movies outdoors this summer in an attempt to generate buzz. Universal CityWalk offered a free "Summer Drive-In Movie" series near the Hard Rock Cafe there. A James Bond film series screened in a commercial courtyard in Pasadena's Old Town. In Colorado, so many cities have outdoor film series that one event producer, a former dot-commer, has launched the Outdoor Cinema Network, a Web site (www.outdoorcinema.com) to help them market themselves.

In San Jose, meanwhile, a bootleg outdoor movie night inaugurated by bored bar patrons in the late 1990s has blossomed into two outdoor cinema programs subsidized by downtown revitalization money. The programs have, in turn, inspired the developer of a new high- end commercial and residential project, Santana Row, to build outdoor movies into the infrastructure of the district's shopping strip, a move that merchants say has bumped business up by 25% or more on film nights.

Now, with three venues where moviegoers can gather in lawn chairs and on blankets on warm nights, officials are considering a fourth modified cinema under the stars for San Jose's new City Hall, which is scheduled for completion in 2005 and which will feature a large plaza and glass-domed rotunda.

Lynn Rogers, arts program officer for the San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs, says the aim is to give citizens a sense of ownership of their public spaces.

"It's a great way," she said, "for people in a community to commune."

The rise in urban movies by moonlight came just as suburban drive-ins were being declared extinct. In 1958, more than 4,000 drive-ins dotted the United States, but the cable and video revolution had put all but a few hundred out of business by about 1985.

In the '90s, city planners and others became intrigued with the idea of open-air movies as a way to bring crowds back to neglected downtowns, but most had imagined such events to be too costly. The massive screens required thousands of dollars' worth of rented scaffolding; the special projectors and speakers called for extra security and insurance; and some theater owners feared that the competition might cannibalize the box office at the local art house.

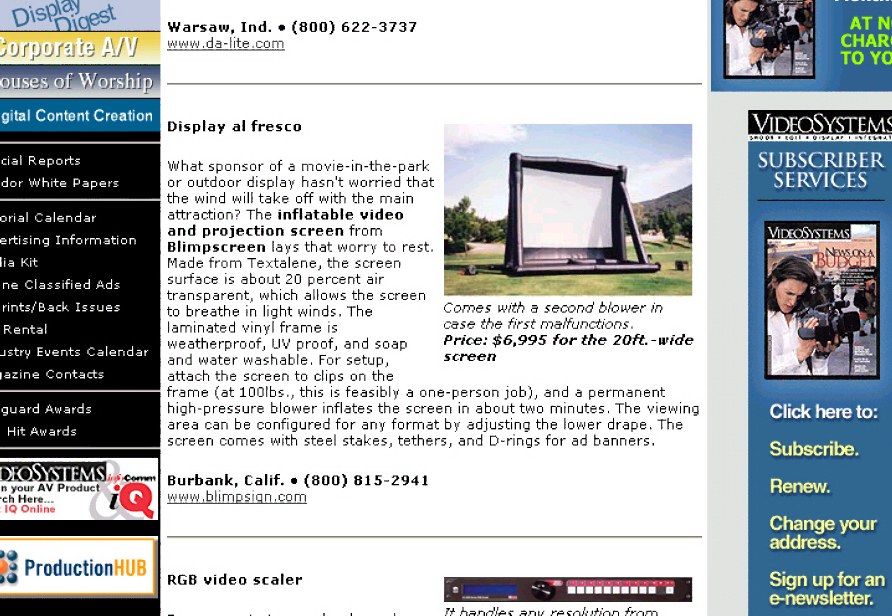

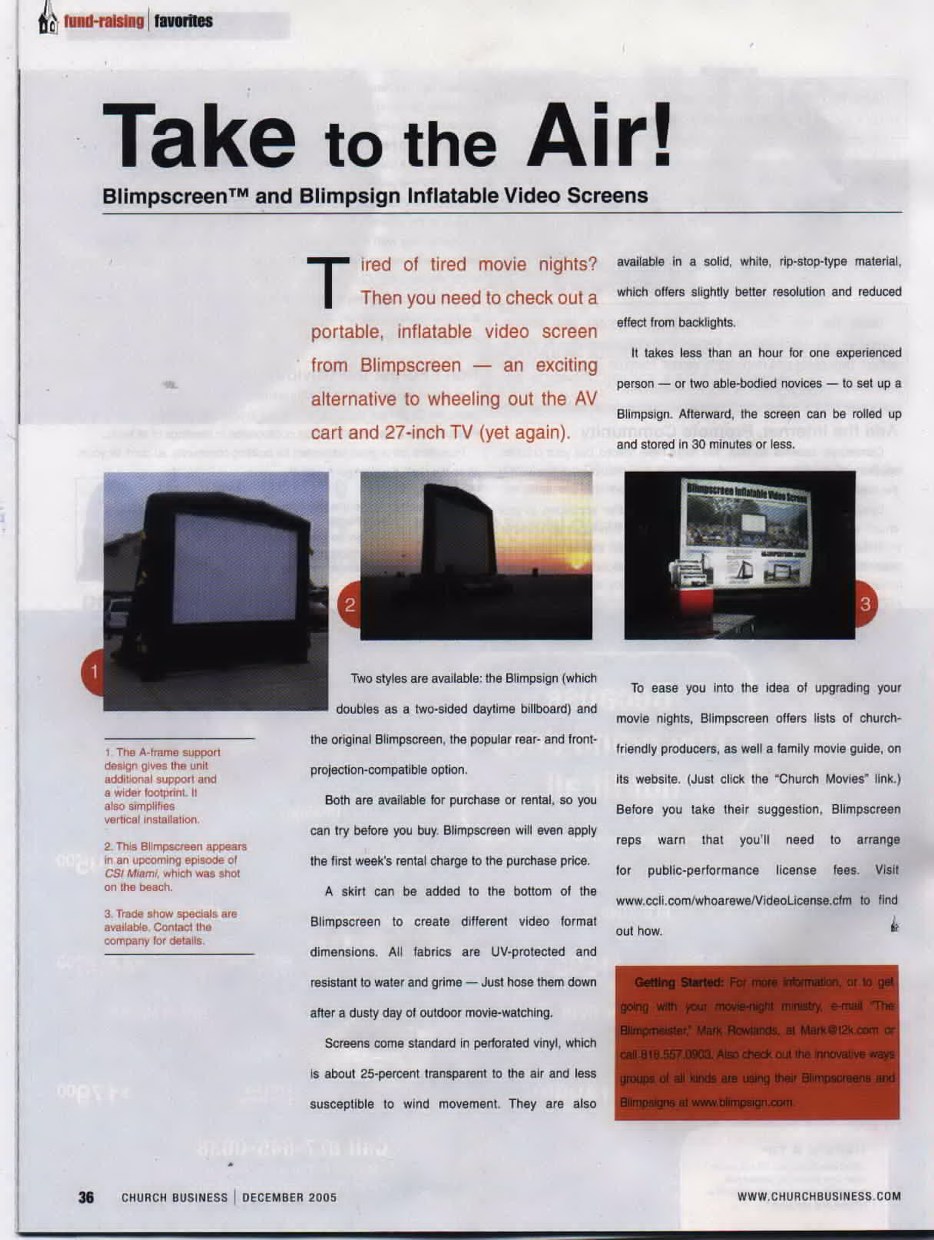

Innovation, however, was underway. In Silicon Valley, dot-commers were rigging up after-hours movies with DVDs, laptops and office PowerPoint projectors. Ad hoc "micro-cinemas" were appearing in bars, on college campuses and on rooftops in Los Angeles and New York. Meanwhile, equipment was becoming more powerful and cheaper, from the projectors to massive inflatable screens from Europe that could be blown up on site like bounce houses at children's birthday parties.

Ideas spread on the Internet and via word of mouth.

The outdoor screenings did not, as it turned out, cut into audiences at local multiplexes and art houses, although discount theaters did appear to lose market share to outdoor cinema, Deutsch said.

There have been other snags, though. Even at lowered costs, promoters say, outdoor movies can run as much as $3,000 or more per film depending on the size of the venue, and not all films will bring out the crowds. (On the other hand, some films have taken on new life as outdoor cinema classics — "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" has become a standard on the blanket-and-lawn-chair circuit.)

Some communities aren't receptive: In Jacksonville, Fla., for example, a preservation group's effort to revive a historic but long blighted neighborhood with an outdoor cinema fizzled in 2001 after a few movies. The preservationists blamed Sept. 11, saying no one felt like coming out after the terrorist attacks. But Tim Massett, the film buff who helped set up the program, offered a different view: "Only the residents would come out, and not even some of them because they didn't want to be out on Main Street. It was fun while it lasted, but it was a very tainted neighborhood."

Then there are the audiences, which sometimes need to be reminded to silence mobile phones, keep the view clear for the people down on the grass and leave pets at home if the animals are inclined to yelp should someone trip over them in the dark.

"At one of our events — I think it was a showing of 'Top Gun' in Fairfax, Va. — a man was smoking and a lady asked him to quit, and when he said no, she grabbed the cigarette out of his mouth and the dude turned around and slapped her," Deutsch said. "We had to throw the both of them out."

For all that, however, the form appears to be spreading, particularly in temperate venues where screenings can run well into the autumn months. There are outdoor cinemas on Main Streets and in warehouse districts, in Rust Belt cities and in Sun Belt suburbs. None charges more than a modest admission — in fact, most are free, underwritten by public subsidies, sponsors or corporate marketing budgets. Some are seasonal, some are year-round.

Foreign Cinema restaurant in San Francisco became a dot-com-era magnet in the late '90s with outdoor classics screened during dinner. At the boutique hotel Habitat in Mexico City, guests at a night reception watched from the rooftop bar this summer as a Charlie Chaplin movie played on the wall of an adjacent mid-rise.

In Silicon Valley, Chris Esparza, who owned a jazz club in languishing downtown San Jose, became an outdoor cinema booster in 1998 after he and some regulars got into a conversation over the paucity of local urban night life. Someone asked: Why couldn't San Jose be more like the town in "Cinema Paradiso," the beloved Italian film in which everyone gathers to watch movies under the stars on hot nights? One thing led to another.

"We borrowed some equipment from a guy I knew who did videos for raves," said Esparza, now 36 and the owner of an events planning business that specializes in nonprofit and civic projects. "We got some speakers on sticks, and someone we knew happened to have a 35-millimeter copy of 'Blade Runner.'

"We showed it at dusk in the back of this parking lot that had walls on three sides. We didn't have a permit, and we were probably in violation of that FBI warning you see when you play a rented movie. But the whole thing probably cost us a hundred bucks, and even without any advertising, about 75 people showed up."

Today, Gypsy Cinema is an annual six-film summer event underwritten by about $12,000 in public funds from the city's redevelopment and cultural affairs budgets. A second outdoor film series, featuring more mainstream titles, has been spun off and is being run by another events company.

Esparza's firm, Giant Creative Services, meanwhile, has helped the developers of Santana Row launch their own outdoor summer film program, designed to make shoppers look at the freshly minted complex as a sort of neighborhood rather than a mundane mall. Old and new classics — "Casablanca," "Bridget Jones's Diary," "The Matrix" — have been shown each Wednesday during the spring and summer for the last year on a massive screen in a grassy plaza surrounded by cafes and restaurants.

"The idea was mainly to say welcome — not necessarily 'Bring your wallet' but 'We're here for you when you're ready to shop,' " said Bill Billings, an area director for Maggiano's Little Italy, a chain that operates a restaurant abutting the plaza. The eatery's 17 cinema-view patio tables quickly became the hottest Wednesday night ticket in San Jose.

"It turned a Wednesday into a Saturday for us, which is a big deal in the restaurant business," he said. "I'd say we had a 20% to 25% increase in business, easy. People were almost bribing the maitre d', and local celebrities and politicians were coming to us, asking for [those tables] as favors. Folks were asking for packages of food to go so they could eat outside on the plaza. There was an early wave that would come and eat before the show started at sundown."

Billings said the festive atmosphere spilled over to neighboring merchants, tripling sales at the nearby Starbucks and creating an opportunity for other food vendors who set up booths for popcorn and snacks. Audiences for the shows have ranged from 300 to 500 a night, he said. They come not just for the picture, he said, but to be together "under the stars in some of the best weather in the world with your neighbors, who, until now, you've never met."

In San Francisco, redevelopment authorities hope that such a mood will help resuscitate the Lower Fillmore, the onetime jazz mecca where the Ali-Foreman film was screened in a vacant lot.

"It's all about creating buzz," said Don Capobres, senior project manager at the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. "Outdoor cinemas create such a dramatic scene: The sun's going down, this huge screen is going up — even the weather plays into the drama here, because you have these flames from the space heaters. People go by in cars and buses, and it makes them want to stop and ask, 'Why are all these people hanging out in the fog here? What's going on?' "

It's a long shot — the district has been singing the blues for decades — and yet it seems to be working. On the night of the boxing film, the biggest topic of conversation was what had become of, and what could be done about, the neighborhood. One man noted that this corner had housed a Black Panthers office in his boyhood; another noted the calming effect the blue light of the cinema seemed to have on the local street people.

"This is like something you'd see in, well, the movies," said Rebecca Atwater, a 44-year-old firefighter, "where a bunch of strangers end up in some barren place and actually end up having a good time."